Byron Sharp’s How Brands Grow: What Marketers Don’t Know was an eye opener for me, because he was right — there was a lot of stuff that I, as a marketer, did not know.

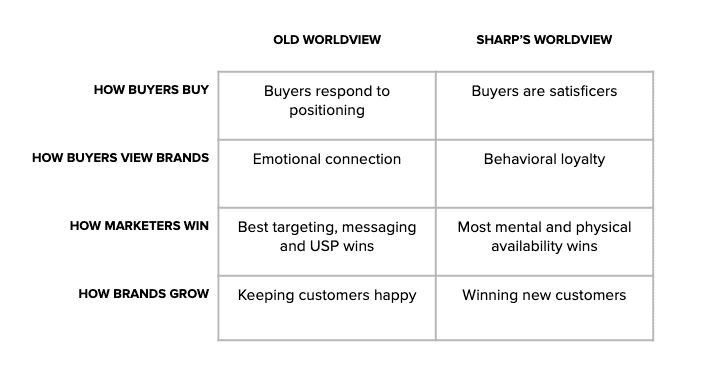

Sharp is basically like: “Hey marketers, your model of how marketing works is all wrong. You’ve been trained that good marketing and brand growth comes from emphasizing emotions, positioning and loyalty. But it doesn’t work like that.”

Here’s my one-table summary of How Brands Grow:

And here’s my one sentence summary of How Brands Grow:

Brands grow by focusing on new customer acquisition, driven by increasing mental and physical availability, resulting in behaviorally loyal buyers.

Let’s go through these one by one.

In Sharp’s view, marketers are incorrectly trained to think that the ideal outcome of marketing and brand growth is the hyperloyal buyer, the one who tattoos your logo on their arm and evangelizes your brand to their friends.

This is captured in versions of this statement that we’ve all heard:

Acquiring new customers is X times more expensive than keeping your current customers.

The implication is that growth comes from retention and driving repurchase from existing customers.

Sharp rejects this sentiment for a few several reasons: (1) the study on which it was based has dubious methodology and (2) it contradicts how market dynamics work. It’s one of those proverbs that have kind of crept into mainstream marketing, and is unquestioned because it has a nice “truthiness” to it.

Instead, Sharp says that your brand’s growth is going to come from light buyers — or nonconsumers.

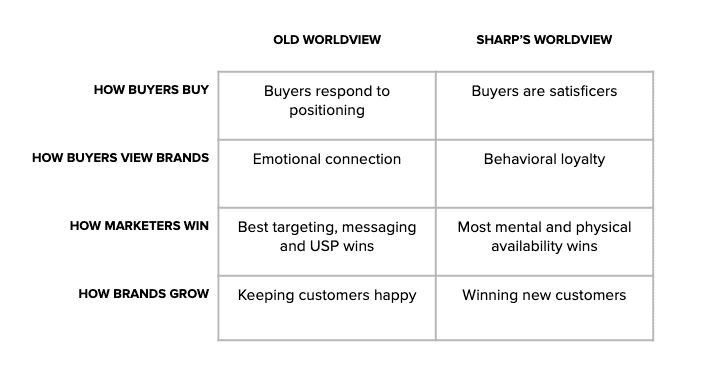

This isn’t from the book, but here’s a diagram I made to try to better understand this:

If you just focus on preventing churn or increasing repurchase rates, you’re only working within the red bubble — there’s only so much growth available there.

If your goal is to grow a brand and getting more business, increasing the size of the “knows your brand” bubble is the best use of your time and resources.

One big reason why this happens is because you compete with things outside of just the other brands in your category. Netflix CEO Reed Hastings has a great way of thinking about this when asked about Disney+ and competition. He understands that consumers will probably subscribe to multiple services, or hop back and forth between services, but he views his real opportunity as flipping “light buyers” (skip to 1:50)

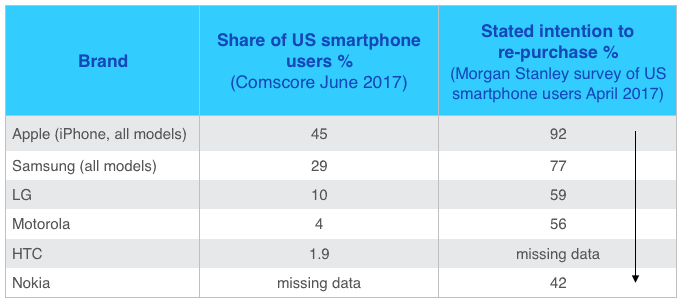

People are satisficers. We take mental shortcuts. We are prefer things that have high cognitive ease.

Therefore, Marketers should focus less on differentiation — obsessing over the perfect articulation of your USP — and more on distinctiveness: being unique and easy to recall.

Sharp emphasizes the importance of having high mental availability and physical availability. I had a tough time really internalizing what this means, but here’s my shot at what each of these mean:

Mental availability refers to the amount of “brain space” a brand takes up in your head. The book primarily has FMCG brands examples, so Sharp describes this in terms of advertising campaigns and packaging. But it could also mean SEO footprint, content marketing, podcast downloads. More brain space = easier to recall during a buying situation.

Physical availability refers to a brand’s presence during a buying situation. Examples of low physical availability: Being out of stock at the grocery store. Your website crashing on Black Friday. Not being on Amazon when your buyers are expecting you to be there.

What this means for you as a marketer:

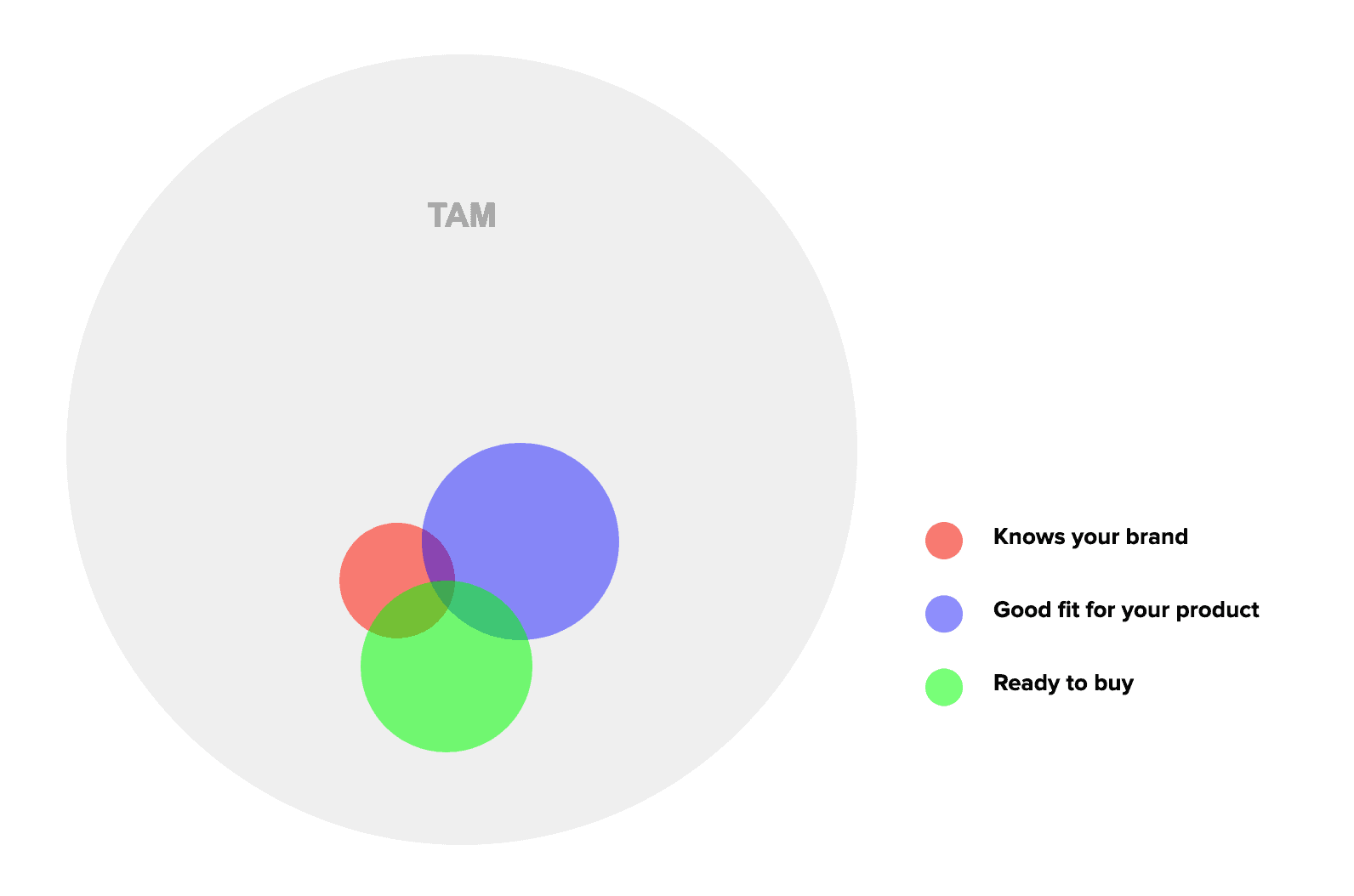

Sharp “debunks” some marketing mythology — like the idea that buyers are emotionally loyal (think: Harley Davidson buyers getting the brand tattoos.)

While that may be true in some outlier cases, the vast majority of “loyal” buyer behavior looks something like this:

I need to buy detergent.

Okay, I’ll just get the same brand I always get.

I’ve been buying it for years and nothing has gone wrong, so I’ll just buy it again.

This is consistent with the view that people are satisficers, we use heuristics, we hate thinking if we don’t have to. If something is good enough, even if it’s not the objectively best solution for our needs, we’ll go forward with it, because we’d rather think about other stuff.

A huge part of the book is Sharp’s exploration of the Double Jeopardy Law: which says that loyalty is a function of your market share. It’s called Double Jeopardy because brands with high market share have the most loyalty, which then means that brands with low market share also have the least loyalty.

What does this mean for you as a marketer?

If you’re reading this because you’re thinking of buying this book — you should just go ahead and buy it. It’s a dense read full of insight.

Here are a few more ideas that stuck with me, but I couldn’t find a place for in the above summary: